Optometrists to give anti-VEGF?

To cope with the growing treatment crisis, the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Ophthalmologists (RANZCO) has backed the right for ophthalmologists to train hospital-based optometrists to give intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) injections.

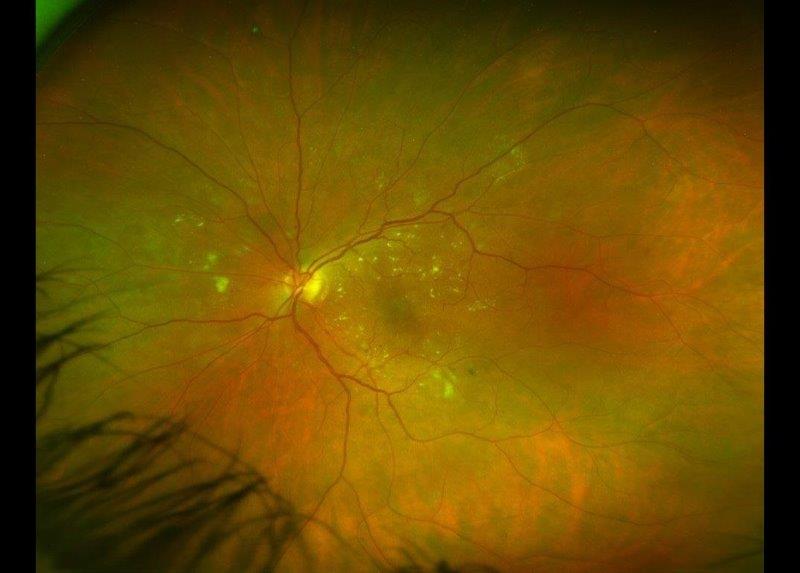

The introduction of anti-VEGF injections has revolutionised the treatment of patients with neovascular age-related macular degeneration (AMD), diabetic macular oedema and retinal vein occlusions. But with an increasingly elderly population, demand is outstripping the health service’s ability to provide timely treatments, leading to some patients going blind unnecessarily.

In some New Zealand District Health Boards (DHBs), special nurse practitioners have been trained to give injections, but this has not been anywhere near enough to cope with demand, especially in poorer regions such as Gisborne, said Gisborne-based ophthalmologist and Otago University clinical senior lecturer Dr Graham Wilson. “The big issue here is that we have one eye doctor for 50,000 people, whereas the New Zealand average is one for 33,000. Also, we have poorer socioeconomic stats, and 47% of the DHB is Māori who we know are more likely to get diabetes and retinopathy.”

Revealing RANZCO’s support at an optometrists’ dinner in Auckland, Dr Wilson said blindness is down 50% because of anti-VEGF injections, but the increased treatment burden is putting a massive strain on overworked hospital staff and health budgets.

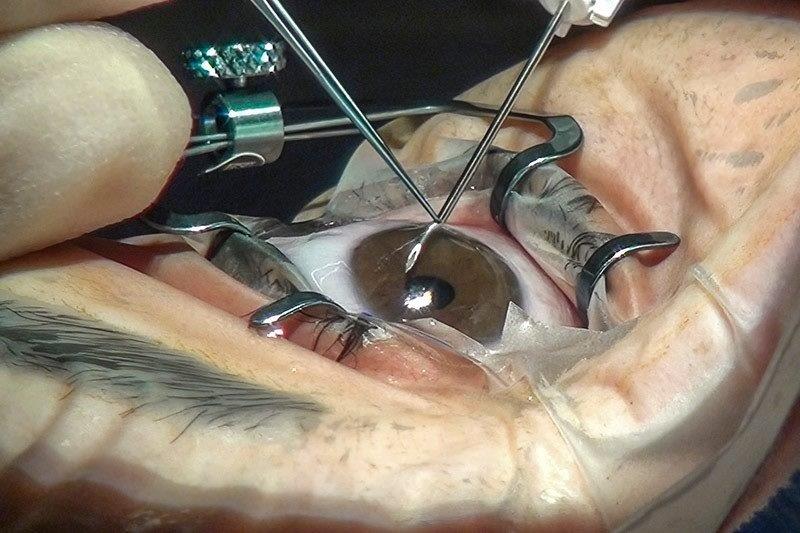

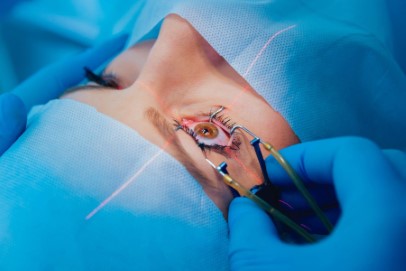

To cope with demand, at the request of his DHB, Dr Wilson employed four optometrists, two for glaucoma, one for paediatrics and one for AMD and diabetes, whom he began to train to inject. However, this led to some criticism relating to optometrists’ lack of training with needles and sterile techniques. A bit of toing and froing resulted, with Dr Wilson pointing out there was a significant patient population in Gisborne at risk of going blind because of a lack of funds and people to treat them.

“The rate of endophthalmitis after these injections is about one in 3,000 and that doesn’t relate to the skill of the practitioner. I’ve trained nine registrars to inject. I’ve trained a nurse to inject, who’s done well over 1,000 injections now, so surely I can train an optometrist who knows the anatomy and physiology of the eye well.”

The RANZCO Board concurred and is now supporting optometrists giving injections within a DHB setting under strict conditions, including being under the direct supervision of an ophthalmologist, making no clinical decisions and being trained in phlebotomy, sterile techniques and first aid. To support this, RANZCO will be issuing new guidelines, based on the UK guidelines, where optometrists have been allowed to give injections for some time.

“RANZCO believes that nurses can adequately cover the current shortfall that exists in some DHBs. If in time this proves not to be the case, for example in more remote DHBs with less availability of nurse injectors, then there may be a need to train other allied health professionals such as optometrists or orthoptists,” said Dr David Andrews, CEO of RANZCO. “The intention is that all intravitreal injectors will work under the supervision of an ophthalmologist in a public hospital. There is no apparent need for allied health professionals to perform intravitreal injections in private practice, whether under supervision or alone.”

“We now have the support of the DHB, the support of RANZCO head office in Sydney, the support of the Ministry of the Health, and the NZAO (New Zealand Association of Optometrists) is completely behind us,” said Dr Wilson. “A lot more patients will go blind from not having injections than from having a trained optometrist injecting - it’s a very simple equation.”

Holding up the scope change, however, is New Zealand regulatory body, the Optometrists and Dispensing Opticians Board (ODOB), which needs to specify and prescribe qualifications for a change in an optometrist’s scope of practice. Though Dr Wilson said the ODOB was putting some thought into this and it looked like a positive outcome would soon result.

ODOB chair Jayesh Chouhan acknowledged Dr Wilson had recently told the ODOB that RANZCO was supportive of optometrists playing a greater role in DHBs. “ODOB is pleased to be informed of this, as having their support is extremely important. The ODOB is currently looking at ways of implementation. This type of change requires a lot of attention to detail and we need to ensure robust measures are taken to ensure safe and competent practise. We are aiming to share further information with stakeholders and practitioners soon.”

NZAO president Rochelle van Eysden said RANZCO’s support was an exciting step for the industry. “It means hospital optometrists, with the support of the consultant, will be allowed to do more in the hospital eye clinic, with the ultimate goal of making life better for patients. We recognise that the overarching health and safety regulation of how this will work under Health Practitioners Competence Assurance Act 2003 is the responsibility of the ODOB, although individual DHBs and their individual lead ophthalmologists will have discretion, as they currently do, in regard to who does what actual jobs in their hospital teams within the health and safety guidelines of their DHB/RANZCO.”

But injecting will not be for every optometrist, said Wilson. “It’s all about being clever, flexible and inventive to best serve a particular region in a collaborative way.”